Guidelines on the Evaluation and Treatment of Patients with Thoracolumbar Spine Trauma

1. Introduction and Methodology

download pdf Neurosurgery, 2018

Sponsored by: Congress of Neurological Surgeons and the Section on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves in collaboration with the Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care

Endorsed by: The Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS)

John E. O’Toole, MD, MS1, Michael G. Kaiser, MD,2, Paul A. Anderson, MD3, Paul M. Arnold, MD4, John H. Chi, MD, MPH5, Andrew T. Dailey, MD6, Sanjay S. Dhall, MD7, Kurt M. Eichholz, MD8 , James S. Harrop, MD9, Daniel J. Hoh, MD10, Sheeraz Qureshi, MD, MBA11, Craig H. Rabb, MD12, and P. B. Raksin, MD13

1Department of Neurological Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

2Department of Neurosurgery, Columbia University, New York, New York

3Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin

4Department of Neurosurgery, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, Kansas

5Department of Neurosurgery, Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

6Department of Neurosurgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah

7Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California

8St. Louis Minimally Invasive Spine Center, St. Louis, Missouri

9Departments of Neurological Surgery and Orthopedic Surgery, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

10Lillian S. Wells Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

11Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

12Department of Neurosurgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah

13Division of Neurosurgery, John H. Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County and Department of Neurological Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Correspondence:

John E. O’Toole, MD, MS

Professor of Neurosurgery

Rush University Medical Center

1725 West Harrison St. Suite 855

Chicago, IL 60612

E-mail: john_otoole@rush.edu

Keywords: clinical practice guideline, lumbar fracture, thoracic fracture, thoracolumbar fracture

No part of this manuscript has been published or submitted for publication elsewhere.

Disclaimer of Liability

This clinical systematic review and evidence-based guideline was developed by a multidisciplinary physician volunteer task force and serves as an educational tool designed to provide an accurate review of the subject matter covered. These guidelines are disseminated with the understanding that the recommendations by the authors and consultants who have collaborated in their development are not meant to replace the individualized care and treatment advice from a patient's physician(s). If medical advice or assistance is required, the services of a competent physician should be sought. The proposals contained in these guidelines may not be suitable for use in all circumstances. The choice to implement any particular recommendation contained in these guidelines must be made by a managing physician in light of the situation in each particular patient and on the basis of existing resources.

ABSTRACT

Background: The thoracic and lumbar (“thoracolumbar”) spine are the most commonly injured region of the spine in blunt trauma. Trauma of the thoracolumbar spine is frequently associated with spinal cord injury and other visceral and bony injuries. Prolonged pain and disability after thoracolumbar trauma present a significant burden on patients and society.

Objective: To formulate evidence-based clinical practice recommendations for the care of patients with injuries to the thoracolumbar spine.

Methods: A systematic review of the literature was performed using the National Library of Medicine PubMed database and the Cochrane Library for studies relevant to thoracolumbar spinal injuries based on specific clinically oriented questions. Relevant publications were selected for review.

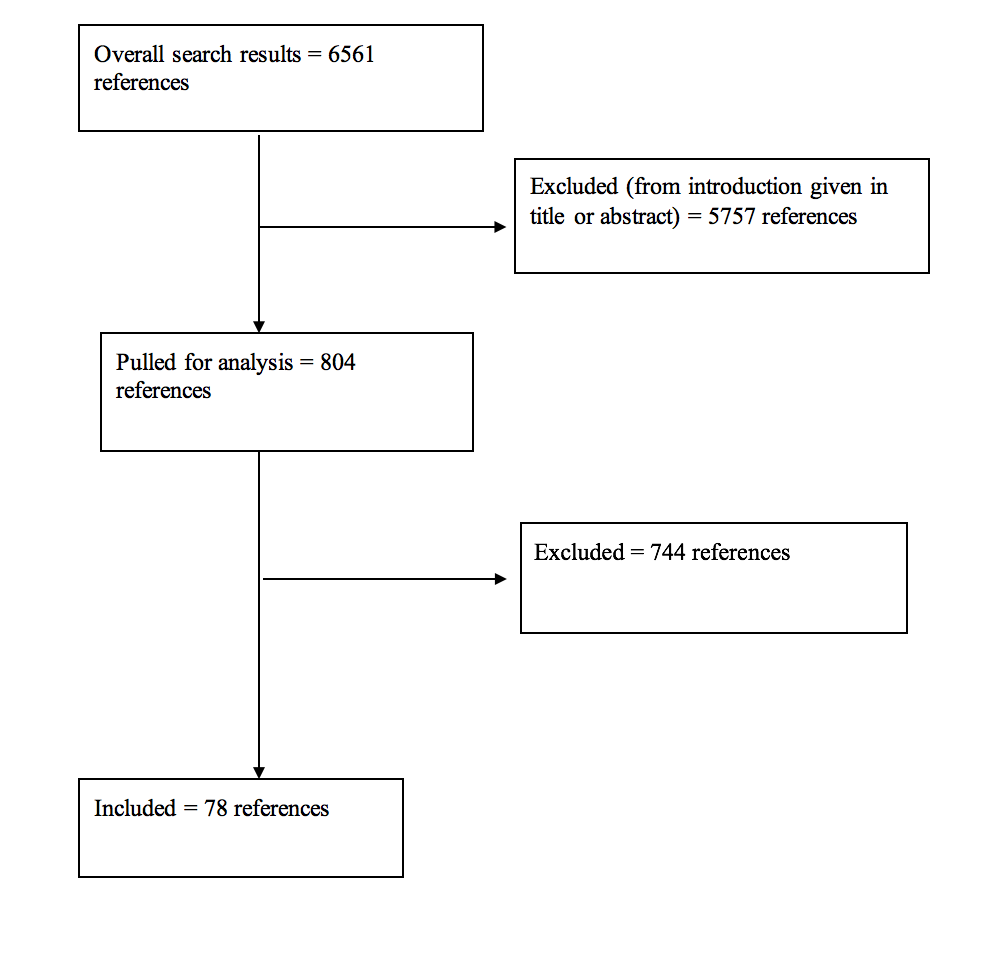

Results: For all of the questions posed, the literature search yielded a total of 6561 abstracts. The task force selected 804 articles for full text review, and 78 were selected for inclusion in this overall systematic review.

Conclusion: The available evidence for the evaluation and treatment of patients with thoracolumbar spine injuries demonstrates considerable heterogeneity and highly variable degrees of quality. However, the workgroup was able to formulate a number of key recommendations to guide clinical practice. Further research is needed to counter the relative paucity of evidence that specifically pertains to patients with only thoracolumbar spine injuries.

INTRODUCTION

Goals and Rationale

Traumatic injuries of the thoracic and lumbar spine (“thoracolumbar”) occur in approximately 7% of all blunt trauma patients and comprise 50% to 90% of the 160,000 annual traumatic spinal fractures in North America.1-5 Up to 25% of patients with thoracolumbar fractures have concomitant spinal cord injury.1,4 Long-term care of patients with persistent disability after thoracolumbar trauma represents a significant burden on society’s health care resources.1,2,4-6 In addition, these patients frequently have multiple visceral and bony injuries, and treatment decision-making can be quite challenging4,6 For the purposes of this guideline, “thoracolumbar” includes the distinct regions of the rigid thoracic spine (T1-10), transitional thoracolumbar junction (T10-L2), and flexible lumbar spine (L3-5). Patients with injuries to these various spinal regions are frequently studied together; therefore, this pooling is needed to more successfully assess the content of the evidence base and allow for practical clinical implementation of the recommendations formulated. The rationale for examining injuries of the thoracolumbar spine separate from injuries of cervical spine lies in the distinct anatomic, physiologic, and epidemiologic characteristics of these 2 groups of patients. Thoracolumbar injuries are more common, concomitant visceral injuries are more frequently seen in thoracolumbar trauma, the types of fractures encountered are anatomically unique, the vascular supply of the thoracic spinal cord is more tenuous than the cervical spinal cord, and surgical decision-making and surgical procedures are different in the two populations.1-6

There remains a lack of consensus on a number of issues surrounding the care of these patients, including 1) formal injury classification systems; 2) appropriate radiological evaluation; 3) neurological assessment instrument; 4) systemic treatments for blood pressure and spinal cord injury management; 5) venous thromboembolism prophylaxis; 6) nonoperative versus operative management; 7) choice of surgical approach; 8) timing of surgical treatment; and 9) novel surgical techniques.1-3,5-11The American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS)/Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) Section on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves and the Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care initiated this effort to develop a clinical practice guideline to answer key clinical questions regarding the care of patients with thoracolumbar trauma using the available evidence base and employing a rigorous guideline elaboration methodology. In particular, specific patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) questions were posed that the workgroup and sponsoring sections felt were the most pertinent to, and in some cases the most controversial, in the routine clinical care of these patients. These PICO questions were formulated before commencing with any literature search or evidence abstraction.

Ultimately, this clinical guideline was created to improve patient care by outlining the appropriate information gathering and decision-making processes involved in the evaluation and treatment of patients with thoracolumbar spine trauma. The surgical management of these patients often takes place under a variety of circumstances and by various clinicians. This guideline was created as an educational tool to guide qualified physicians through a series of diagnostic and treatment decisions in an effort to improve the quality and efficiency of care.

METHODS

The guidelines task force initiated a systematic review of the literature relevant to the diagnosis and treatment of patients with thoracolumbar trauma. Through objective evaluation of the evidence and transparency in the process of making recommendations, this evidence-based clinical practice guideline was developed for the diagnosis and treatment of adult patients with thoracolumbar injury. These guidelines are developed for educational purposes to assist practitioners in their clinical decision-making processes.

Literature Search

The task force members identified search terms/parameters, and a medical librarian implemented the literature search, consistent with literature search protocols, using the National Library of Medicine PubMed database and the Cochrane Library (which included the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effect, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Health Technology Assessment Database, and the National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database) for the period from January 1, 1946 to March 31, 2015, using the search strategies provided in each paper of this guideline series.

RESULTS

A total of 6561 studies were yielded from the literature searches for all chapters of this guideline. Task force members reviewed all abstracts yielded from the literature search and identified a total of 804 studies for full text review and extraction, addressing the clinical questions in accordance with the literature search protocols (provided in each chapter). Task force members identified the best research evidence available to answer the targeted clinical questions. When level I, II, or III literature was available to answer specific questions, the task force did not review level IV studies. A total of 78 studies were selected for inclusion in the systematic review (Appendix I). Selection of studies for full-text review were conducting by 2 members of the workgroup (unique for each chapter) in conjunction with CNS Guidelines staff. Disagreements regarding selection of abstracts for full-text review were resolved by consensus under the guidance of the workgroup chairs.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Articles were retrieved and included only if they met specific inclusion/exclusion criteria. These criteria were also applied to articles provided by guideline task force members who supplemented the electronic database searches with articles from their own files. To reduce bias, these criteria were specified before conducting the literature searches.

Articles that did not meet the following criteria, for the purposes of this evidence-based clinical practice guideline, were excluded. To be included as evidence in the guideline, an article had to be a report of a study that:

- Investigated patients with thoracolumbar injuries;

- Included patients ≥18 years of age;

- Enrolled ≥80% of thoracolumbar injuries (studies with mixed patient populations were included if they reported results separately for each group/patient population);

- Was a full article report of a clinical study;

- Was not an internal medical records review, meeting abstract, historical article, editorial, letter, or commentary;

- Appeared in a peer-reviewed publication or a registry report;

- Enrolled ≥10 patients per arm per intervention (20 total) for each outcome;

- Included only human subjects;

- Was published in or after 1946;

- Quantitatively presented results;

- Was not an in vitro study;

- Was not a biomechanical study;

- Was not performed on cadavers;

- Was published in English;

- Was not a systematic review, meta-analysis, or guideline developed by others*

- Was a case series (therapeutic study) where higher level evidence exists.

Rating Quality of Diagnostic Evidence

The guideline task force used a modified version of the North American Spine Society’s evidence-based guideline development methodology.12The North American Spine Society methodology uses standardized levels of evidence (Appendix II) and grades of recommendation (Appendix III) to assist practitioners in easily understanding the strength of the evidence and the recommendations within the guidelines. The levels of evidence range from level I (high-quality randomized controlled trial) to level IV (case series). Grades of recommendation indicate the strength of the recommendations made in the guideline based on the quality of the literature. Levels of evidence have specific criteria and are assigned to studies before developing recommendations. Recommendations are then graded based upon the level of evidence. To better understand how levels of evidence inform the grades of recommendation and the standard nomenclature used within the recommendations, see Appendix III.

Guideline recommendations were written using a standard language that indicates the strength of the recommendation. “A” recommendations indicate a test or intervention is “recommended”; “B” recommendations “suggest” a test or intervention; “C” recommendations indicate that a test or intervention or “is an option.” “Insufficient evidence” statements clearly indicate that “there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for or against” a test or intervention. Task force consensus statements clearly state that “in the absence of reliable evidence, it is the task force’s opinion that” a test or intervention may be considered. Both the levels of evidence assigned to each study and the grades of each recommendation were arrived at by consensus of the workgroup using up to three rounds of voting when necessary.

In evaluating studies as to levels of evidence for this guideline, the study design was interpreted as establishing only a potential level of evidence. For example, a therapeutic study designed as a randomized controlled trial would be considered a potential level I study. The study would then be further analyzed as to how well the study design was implemented, and significant shortcomings in the execution of the study would be used to downgrade the levels of evidence for the study’s conclusions (see Appendix IV for additional information and criteria).

Revision Plans

In accordance with the Institute of Medicine’s standards for developing clinical practice guidelines and criteria specified by the National Guideline Clearinghouse, the task force will monitor related publications after the release of this document and will revise the entire document and/or specific sections “if new evidence shows that a recommended intervention causes previously unknown substantial harm; that a new intervention is significantly superior to a previously recommended intervention from an efficacy or harms perspective; or that a recommendation can be applied to new populations.”13 In addition, the task force will confirm within 5 years from the date of publication that the content reflects current clinical practice and the available technologies for the evaluation and treatment for patients with thoracolumbar trauma.

DISCUSSION

This guideline yields a number of important recommendations but also highlights the paucity of high-level evidence regarding the care of specifically the thoracolumbar trauma population. Many (if not most) spinal trauma publications contain a high degree of heterogeneity in the populations studied, including levels of injury (mixed cervical and thoracolumbar), mechanisms of injury, anatomical classifications of injury, neurological status at admission, interventions performed, outcomes studied, and follow-up periods. For this guideline, the evidence base allowed only one grade A recommendation: “Surgeons should understand that the addition of arthrodesis to instrumented stabilization has not been shown to impact clinical or radiologic outcomes, and adds to increased blood loss and operative time.” Several grade B and C recommendations were also made, but in many circumstances, the workgroup was left with inconclusive evidence to answer the salient clinical questions posed. In two cases, the workgroup felt compelled to generate recommendations based solely on consensus because of what was perceived as current standard of care with minimal risk posed to the patient (blood pressure management and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis).

Future Research

Each chapter within this guideline explores areas of need for future research for each topic of interest. However, as a general need, future studies should attempt to analyze patients with thoracolumbar injuries separate from those with cervical injuries to better clarify the most effective diagnostic and treatment modalities for these patients in particular.

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, this clinical practice guideline serves as a critical reference for clinicians caring for adult patients with thoracolumbar trauma. This synthesis of the most contemporary evidence using rigorous methodology provides the reader with an important resource to address key questions in routine clinical practice. As with all evidence-based guidelines, however, it should be implemented in conjunction with clinician expertise and patient preferences.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

The task force members were required to report all possible conflicts of interest (COIs) before beginning work on the guideline, using the COI disclosure form of the AANS/CNS Joint Guidelines Review Committee, including potential COIs that are unrelated to the topic of the guideline. The CNS Guidelines Committee and Guideline Task Force Chairs reviewed the disclosures and either approved or disapproved the nomination. The CNS Guidelines Committee and Guideline Task Force Chairs are given latitude to approve nominations of Task Force members with possible conflicts and address this by restricting the writing and reviewing privileges of that person to topics unrelated to the possible COIs. The conflict of interest findings are provided in detail in Appendix V.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The guidelines task force would like to acknowledge the CNS Guidelines Committee for their contributions throughout the development of the guideline and the AANS/CNS Joint Guidelines Review Committee for their review, comments, and suggestions throughout peer review, as well as the contributions of Trish Rehring, MPH, CHES, Senior Manager of Clinical Practice Guidelines for the CNS, and Mary Bodach, MLIS, Guidelines Specialist and Medical Librarian for assistance with the literature searches. Throughout the review process the reviewers and authors were blinded from one another. At this time, the guidelines task force would like to acknowledge the following individual peer reviewers for their contributions: Maya Babu, MD, MBA, Greg Hawryluk, MD, PhD, Steven Kalkanis, MD, Yi Lu, MD, PhD, Jeffrey J. Olson, MD, Martina Stippler, MD, Cheerag Upadhyaya, MD, MSc, and Robert Whitmore, MD.

Disclosures

These evidence-based clinical practice guidelines were funded exclusively by the Congress of Neurological Surgeons and the Section on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves in collaboration with the Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care, which received no funding from outside commercial sources to support the development of this document.

Appendix I. Article Inclusions and Exclusions

Included and Excluded Articles Flowchart

Appendix II. Rating Evidence Quality

Levels of Evidence for Primary Research Questiona

Therapeutic studies – Investigating the results of treatment

| Types of studies |

|

|

|

|

| Therapeutic studies – Investigating the results of treatment |

Prognostic studies – Investigating the effect of a patient characteristic on

|

Diagnostic studies – Investigating a diagnostic test |

Economic and decision analyses – Developing an economic or decision |

| Level I |

- High-quality randomized trial with statistically significant difference or no statistically significant difference but narrow confidenceintervals

- Systematic reviewb of level I RCTs (and study results were homogenousc)

|

- High-quality prospective studyd (all patients were enrolled at the same point in their disease with

≥80% follow-up of enrolled patients)

- Systematic reviewb of level I studies

|

- Testing of previously developed diagnostic criteria on consecutive patients (with universally applied reference “gold” standard)

- Systematic reviewb of level I studies

|

- Sensible costs and alternatives; values obtained from many studies; with multiway sensitivity analyses

- Systematic reviewb of level I studies

|

|

| Level II |

- Lesser quality RCT (e.g., ≤80% follow-up, no blinding, or improper randomization)

- Prospectived comparative studye

- Systematic reviewb of level II studies or level I studies with inconsistent results

|

- Retrospectivef study

- Untreated controls from an RCT

- Lesser quality prospective study (e.g., patients enrolled at different points in their disease or

≤80% follow-up)

- Systematic reviewb of level II studies

|

- Development of diagnostic criteria on consecutive patients (with universally applied reference “gold” standard)

- Systematic reviewb of level II studies

|

- Sensible costs and alternatives; values obtained from limited studies; with multiway sensitivity analyses

- Systematic reviewb of level II studies

|

|

| Level III |

- Case control studyg

- Retrospectivef comparative studye

- Systematic reviewb of level III studies

|

|

- Study of nonconsecutive patients; without consistently applied reference “gold” standard

- Systematic reviewb

|

- Analyses based on limited alternatives and costs; and poor estimates

- Systematic reviewb of level III studies

|

|

| Level IV |

| Case seriesh |

Case series |

- Case-control study

- Poor reference standard

|

- Analyses with no sensitivity analyses

|

RCT, Randomized controlled trial.

aA complete assessment of quality of individual studies requires critical appraisal of all aspects of the study design.

bA combination of results from ≥2 previous studies.

cStudies provided consistent results.

dStudy was started before the first patient enrolled.

ePatients treated one way (e.g., instrumented arthrodesis) compared with a group of patients treated in another way (e.g., unsintrumented arthrodesis) at the same institution.

fThe study was started after the first patient enrolled. gPatients identified for the study based on their outcome, called “cases” (e.g., pseudoarthrosis) are compared to those who did not have outcome, called “controls” (e.g., successful fusion).

hPatients treated one way with no comparison group of patients treated in another way.

Appendix III. Linking Levels of Evidence to Grades of Recommendation

| Grade of recommendation |

Standard language |

Levels of evidence |

| A |

Recommended |

Two or more consistent level I studies |

| B |

Suggested |

One level I study with additional supporting level II or III studies |

Two or more consistent level II or III studies |

| C |

Is an option |

One level I, II, or III study with supporting level IV studies |

Two or more consistent level IV studies |

|

Insufficient

(insufficient or conflicting evidence) |

Insufficient evidence to make recommendation for or against |

A single level I, II, III, or IV study without other supporting evidence |

>1 study with inconsistent findingsa |

aNote that in the presence of multiple consistent studies, and a single outlying, inconsistent study, the Grade of Recommendation will be based on the level of the consistent studies.

Appendix IV. Criteria Grading the Evidence

The task force used the criteria provided below to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the studies included in this guideline. Studies containing deficiencies were downgraded one level (no further downgrading allowed, unless so severe that study had to be excluded). Studies with no deficiencies based on study design and contained clinical information that dramatically altered current medical perceptions of topic were upgraded.

1. Baseline study design (i.e., therapeutic, diagnostic, prognostic) determined to assign initial level of evidence.

2. Therapeutic studies reviewed for following deficiencies:

- Failure to provide a power calculation for an RCT;

- High degree of variance or heterogeneity in patient populations with respect to presenting diagnosis/demographics or treatments applied;

- <80% of patient follow-up;

- Failure to utilize validated outcomes instrument;

- No statistical analysis of results;

- Cross over rate between treatment groups of >20%;

- Inadequate reporting of baseline demographic data;

- Small patient cohorts (relative to observed effects);

- Failure to describe method of randomization;

- Failure to provide flowchart following patients through course of study (RCT);

- Failure to account for patients lost to follow-up;

- Lack of independent post-treatment assessment (e.g., clinical, fusion status, etc.);

- Utilization of inferior control group:

- Historical controls;

- Simultaneous application of intervention and control within same patient.

- Failure to standardize surgical/intervention technique;

- Inadequate radiographic technique to determine fusion status (e.g., static radiographs for instrumented fusion).

3. Methodology of diagnostic studies reviewed for following deficiencies:

- Failure to determine specificity and sensitivity;

- Failure to determine inter- and intraobserver reliability;

- Failure to provide correlation coefficient in the form of kappa values.

4. Methodology of prognostic studies reviewed for following deficiencies:

- High degree of variance or heterogeneity in patient populations with respect to presenting diagnosis/demographics or treatments applied;

- Failure to appropriately define and assess independent and dependent variables (e.g., failure to use validated outcome measures when available).

Appendix V. Conflicts of Interest>

| Author |

Potential COI |

| Paul A. Anderson, MD |

- Aesculap: Consultant fee

- SI Bone: Stock shareholder

- Spartec: Stock shareholder

- Expanding Orthopedics: Stock shareholder

- Titan Spine: Stock shareholder

- RTI: Other financial support

- Stryker: Other financial support

- Lumbar Spine Research Society: Board, trustee or officer position (President)

|

| Paul M. Arnold, MD |

- Medtronic: Consultant fee

- Sofamor Danek: Consultant fee

- Spine Wave: Consultant fee

- InVivo: Consultant fee

- Stryker Spine: Consultant fee

- Evoke Medical: Stock shareholder

- Z-Plasty: Stock shareholder

- AO Spine North America: Sponsored or reimbursed travel (for self only)

|

| John H. Chi, MD, MPH |

- DePuy Spine: Consultant fee

- K2M: Consultant fee

|

| Andrew Dailey, MD |

- K2M: Grants/Research support

- K2M: Consultant fee

- Zimmer Biomet: Consultant fee

- Medtronic: Consultant fee

|

| Sanjay Dhall, MD |

- Globus Medical: Honorarium

- Depuy Spine: Honorarium

|

| James S. Harrop, MD |

- DePuy Spine: Consultant fee

- Asterias: Other financial support/Scientific advisor

- Tejin: Other financial support/Scientific advisor

- Bioventus: Other financial support/Scientific advisor

- AO Spine: Board, trustee, or officer position

|

| John E. O’Toole, MD, MS |

- Globus Medical: Consultant fee

- RTI Surgical: Consultant fee

- Theracell, Inc.: Stock shareholder

|

REFERENCES

1. Ghobrial GM, Jallo J. Thoracolumbar spine trauma: Review of the evidence. J Neurosurg Sci 2013;57:115-122.

2. Ghobrial GM, Maulucci CM, Maltenfort M, et al. Operative and nonoperative adverse events in the management of traumatic fractures of the thoracolumbar spine: a systematic review. Neurosurg Focus 2014;37:E8.

3. Joaquim AF, Patel AA. Thoracolumbar spine trauma: Evaluation and surgical decision-making. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 2013;4:3-9.

4. Katsuura Y, Osborn JM, Cason GW. The epidemiology of thoracolumbar trauma: A meta-analysis. J Orthop 2016;13:383-388.

5. Wood KB, Li W, Lebl DR, Ploumis A. Management of thoracolumbar spine fractures. Spine J 2014;14:145-164.

6. Dai LY, Yao WF, Cui YM, Zhou Q. Thoracolumbar fractures in patients with multiple injuries: Diagnosis and treatment-a review of 147 cases. J Trauma 2004;56:348-355.

7. Fu MC, Nemani VM, Albert TJ. Operative treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures: Is fusion necessary? HSS J 2015;11:187-189.

8. Gertzbein SD. Scoliosis Research Society. Multicenter spine fracture study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992;17:528-540.

9. Lopez AJ, Scheer JK, Smith ZA, Dahdaleh NS. Management of flexion distraction injuries to the thoracolumbar spine. J Clin Neurosci 2015;22:1853-1856.

10. Scheer JK, Bakhsheshian J, Fakurnejad S, Oh T, Dahdaleh NS, Smith ZA. Evidence-based medicine of traumatic thoracolumbar burst fractures: A systematic review of operative management across 20 years. Global Spine J 2015;5:73-82.

11. Schroeder GD, Harrop JS, Vaccaro AR. Thoracolumbar trauma classification. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2017;28:23-29.

12. North American Spine Society website. Clinical guidelines. Available at: https://www.spine.org/ResearchClinicalCare/QualityImprovement/ClinicalGu.... Accessed April 16, 2018.

13. Ransohoff DF, Pignone M, Sox HC. How to decide whether a clinical practice guideline is trustworthy. JAMA 2013;309:139-140.

© Congress of Neurological Surgeons

Source: Neurosurgery