Family Letters

Walter E. Dandy, leading neurosurgeon during the first half of this century, corresponded with his parents, John and Rachel Dandy, between the years 1907 and 1914 while he was at the Johns Hopkins medical school (1907 - 1910) and after graduation in 1910 when he began his career on the surgical staff of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Walter E. Dandy, leading neurosurgeon during the first half of this century, corresponded with his parents, John and Rachel Dandy, between the years 1907 and 1914 while he was at the Johns Hopkins medical school (1907 - 1910) and after graduation in 1910 when he began his career on the surgical staff of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

They were an extremely close-knit family, and John and Rachel wrote faithfully to their son each week. Although Walter was busy as a medical student and later as a resident, he tried to do the same. Since there remain only about 300 letters from that seven year period, many were obviously lost. About 50 of Walter Dandy's survive, those written mainly during the three-year period when his parents were living in England (1911 - 1914).

The parents reveal much about their own personalities in their letters, and this in turn gives insights into the personality of their son, as he inherited many of their traits. Their descriptions of life in Sedalia tell much about the world in which he grew up, and their accounts of life in England before World War I describe life in that period.

View the Letters

Dandy's letters describe his early work in neurosurgery, as well as the personalities and politics of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. They also provide little known clues into the origin of the famous Cushing - Dandy lifelong feud, which began as early as 1910.

Walter Dandy's letters as transcribed here were not edited at all. In the interest of brevity, the letters of the parents have been edited. In John and Rachel's letters, much gossip, railroad news, comments about the weather have been deleted unless they reveal something of personalities, relationships, or localities. John Dandy's spelling has been left in the original. A deep and logical thinker, his poor spelling is the only clue to the fact that he left school in the third grade and was largely a self-taught man. In order to make the letters more readable, punctuation was corrected in all the letters.

The project could never have gone forward without the services of Donna Arend, who transcribed the original letters and entered the edits. Donna was always prompt, accurate, and cheerful. All of the original letters, as well as computerized files with the transcribed and edited versions of these letters, are in the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives at Johns Hopkins.

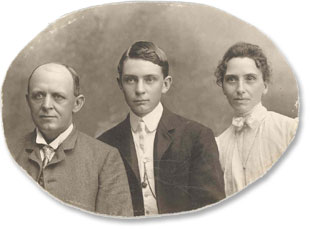

John Dandy

John Dandy was born in 1856 in Tarleton, England, a small village between Southport and Preston in the northwest part of that country. His family can be traced back to the 1500's, when they were farmers, small landowners and yeoman (a somewhat middle-class status). The family was fairly prosperous until the religious upheavals of the 17th century when, as Catholics and recusants, they began to lose their land. John's particular branch of the family was nearly destitute at the time he was born. According to the 1860 census, John was living in a small thatched cottage with his mother, sister, two aunts, and their three children. The three sisters worked as domestic servants, needle women and bread bakers. John left school in the third grade to work as an agricultural laborer, and at age fourteen, he and his mother and sister moved to Barrow-in-Furness in search of work.

Barrow was then a rising steel town and men from all over the British Isles poured into this bustling city looking for jobs in the steel mills and railroad and shipyards. After working in the steel mills, John eventually found work on the Furness Railroad.

In 1883, John left for America with an English friend, Bob Battersby, who had heard about a small town in Missouri called Sedalia, where the Missouri Pacific (MoPac) and Missouri, Kansas and Texas (MKT) railroads were rapidly expanding. Before the Civil War, Sedalia had been a cow town, a center for traders coming out of the Indian Territory bringing their pelts, hides, ponies, etc. After the war was over, the railroads in that part of the country quickly pushed out in all directions, due partly to a need to serve the ever-growing number of European immigrants (mainly the Irish, English, and Germans) who were attracted to cheap land in the West.

John began working for the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad as a fireman, and eventually worked his way up to the prestigious job of engineer. Upon his retirement in 1910, he was the engineer on the crack passenger train, the Katy Flyer. Bob Battersby found work on the Missouri Pacific. Next door neighbors of the Dandy family, Bob and his wife and two children, Stanley and Polly, are mentioned often in the letters.

John married Rachel Kilpatrick in 1885, and they had one child, Walter. When Walter graduated from medical school in 1910, John and Rachel followed him to Baltimore, expecting to make their home near him. Because their son's plans were still unsettled a year later, John and Rachel traveled to England and Ireland to visit family and friends. They stayed abroad three years, returning just as World War I was breaking out in autumn of 1914.

John and Rachel settled in Baltimore in a small house on Arunah Avenue. Their son lived with them from 1914 to 1924 when he was married. John and Rachel led quiet, uneventful lives that continued to center on son and church. Rachel died in 1936 at age 75, and John lived on alone in the house on Arunah Avenue until his death in 1940 at 83.

By today's standards, John would not be considered a particularly successful man, but given his lack of education and other limited opportunities, he was able through hard work, perseverance, and good sense to come a long way toward realizing the American dream. Liberal in his social and political views, he was a lifelong socialist. But mindful of his need to be self-supporting, he learned to invest his money wisely and he was able to live on his investments after his retirement.

By nature, John was friendly, easy-going, and kindly. He had that most admirable and rare quality known as generosity of spirit, and he was loved by all who knew him.

Rachel Kilpatrick Dandy

Rachel Kilpatrick was born in 1861 in Bally Lane, County Armagh in northern Ireland. Her ancestors were Scots-Irish Presbyterians, who settled in Ulster in the 17th century when the English sent Scots and Englishmen to colonize Ireland in order to control the rebellious Irish.

Rachel's parents, David and Mary, owned a small farm and were sufficiently well off to send their children through school. Rachel graduated from a small rural school called Cladymore Academy, and soon after at about age nineteen, she left Ireland and went to live in Barrow. Like the country girls in New England who went to work in the mills, this was probably more out of the desire to escape the monotony, drudgery and poor matrimonial prospects of farm life than from economic necessity.

In Barrow, Rachel worked as a dressmaker and joined a church called the Plymouth Brethren, a fundamentalist Christian sect that rose during the early 1800's to protest formal forms of worship and the union of church and state. It was at a church meeting that she met John Dandy in 1881. Religion was an important part of their lives then, and was to remain so all their lives.

When John left for America in 1883, Rachel promised to follow him when he found work and could send for her. In 1885, she sailed for America alone, met John in St. Louis where they were married the same night. The next day they went to Sedalia, where John had bought a small house on 5th Street. The following year, their son and only child, Walter, was born.

From that day on, her son was the center of Rachel Dandy's life, and as time went on she became increasingly obsessive about him. No detail of his life escaped her scrutiny - his food, clothes, friends, work, etc. In turn, he adored her. He always wanted to find an "old-fashioned girl like Mama."

Rachel had many of the traits that we have come to associate with the Scots-Irish: frugal, industrious, religious and sensible. In temperament, she was the opposite of her husband. He was sociable; she was shy, almost reclusive. He had an even disposition; she had what she called an "Irish temper." He was tolerant; she held everything and everybody to a high standard. His social and political views were liberal; hers were conservative. In spite of their different personalities, they loved each other deeply, and theirs was an unusually happy marriage.

A proud and contented person, Rachel was well satisfied with her lot in life. Not only was she confident of her abilities as mother, cook, and housekeepter, but she knew that she had the best husband in Sedalia and the "best boy on earth." It was of little concern to her that the "English crowd" looked down on her because she was Irish. As she commented in one of her letters, she considered them to be "the same old miserable class of people." Rather than try to ingratiate herself with them, she withdrew to the company of her husband and son.

Rachel died in Baltimore in July, 1936.

Walter Edward Dandy

Walter Edward Dandy was born April 6, 1886 in the small prairie town of Sedalia, Missouri. He was raised in a tiny house on 5th Street, surrounded by English immigrants who, like his father, worked on the railroads.

Walter Edward Dandy was born April 6, 1886 in the small prairie town of Sedalia, Missouri. He was raised in a tiny house on 5th Street, surrounded by English immigrants who, like his father, worked on the railroads.

After graduating in 1903 from Sedalia High School as valedictorian of his class, he entered the University of

Missouri at Columbia. As a junior at the University of Missouri, he enrolled in a 2-year medical program, but in 1910, he took his B.A. and transferred to Johns Hopkins Medical School as a 2nd - year student. He was the first person in either of his parents' families to attend college.

At Hopkins, his ability became apparent very early to several of his professors. Among them was Franklin P. Mall, professor of Anatomy, who entrusted a very early human embryo to Dandy to study. The results of this project were published in 1910 in "A human embryo of seven pairs of somites measuring 2 mm. in length."

Another professor who took an interest in Dandy was Harvey Cushing, who had founded the Hunterian Lab several years earlier and appointed him his first surgical assistant in that lab. Research in the Hunterian at that time focused on the pituitaries of cats and dogs.

Dandy's conflict with Cushing began during this period. Although the true source is sketchy, we do learn from the letters that tensions arose of difference in the conclusions of both men in their research on the pituitary and later, hydrocephalus. Relations between the two men deteriorated to the point that when Cushing left Hopkins to go to Harvard, he decided against taking Dandy with him as he had promised.

Dandy was distressed at this turn of events because he had turned down a position at Hopkins for the following year. However, he stayed on at Hopkins after the Superintendent of the Hospital, Winford Smith, offered him a room there and Dr. Halsted, who considered Dandy one of his most brilliant pupils, appointed him assistant professor of surgery. From that time on, Dandy remained at Hopkins, becoming its leading neurosurgeon until his death at 60 in 1946.

Dandy was distressed at this turn of events because he had turned down a position at Hopkins for the following year. However, he stayed on at Hopkins after the Superintendent of the Hospital, Winford Smith, offered him a room there and Dr. Halsted, who considered Dandy one of his most brilliant pupils, appointed him assistant professor of surgery. From that time on, Dandy remained at Hopkins, becoming its leading neurosurgeon until his death at 60 in 1946.

His contributions to the field of neurosurgery include 159 articles and 5 books, among them a classic text on neurosurgery, "Surgery of the Brain" (1935). The discovery of ventriculography was considered his greatest contribution. He performed over 2000 operations, among them operations for hydrocephalus, brain abscesses, subdural hematoma, trifacial neuralgia, and intervertebral discs.

In 1924 he married Sadie Martin, a dietician at Hopkins Hospital. They had four children, Walter, Jr. (b. 1925), Mary Ellen (b.1927), Kitty (b. 1928), and Margaret (b.1935). He was devoted to his family and had a quiet home life, with occasional winter trips to Florida and summer vacations in West Virginia. He enjoyed golf, bridge, travel, trains, and Civil War history, but by far the major part of this life was spent on his work and family.

Dandy's personality was complicated and confusing to many. It is helpful to understand the personalities of his parents because he was a combination of both. He resembled his father in his kindness, gentleness, and caring for other people. But he was like his mother in his inner-direction, bluntness, short temper, and perfectionism. These traits were often in conflict, and there many who saw only one side or the other. Those who were willing or able to look beneath the surface usually found the often buried generous and loving side.

Dandy's personality was complicated and confusing to many. It is helpful to understand the personalities of his parents because he was a combination of both. He resembled his father in his kindness, gentleness, and caring for other people. But he was like his mother in his inner-direction, bluntness, short temper, and perfectionism. These traits were often in conflict, and there many who saw only one side or the other. Those who were willing or able to look beneath the surface usually found the often buried generous and loving side.